Dialogue: The Conversational Nature of Strategy

Tuesday, June 14th, 2011“To listen is to lean in, softly, with a willingness to be changed by what we hear.â€

Mark Nepo

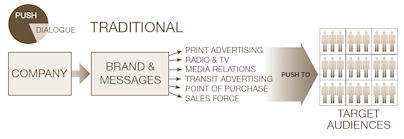

Increasingly strategy must be about dialogue. In a recent article  about the changing nature of strategy and marketing in the “Twenty-Tweens” (our current age), I described three different forms of communication – information sharing, persuasion and dialogue. Information sharing and persuasion are the two forms most people associate with marketing. But the nature of business, the demands of customers and stakeholders are quickly outstripping the capacity of information sharing and persuasion alone to respond.

about the changing nature of strategy and marketing in the “Twenty-Tweens” (our current age), I described three different forms of communication – information sharing, persuasion and dialogue. Information sharing and persuasion are the two forms most people associate with marketing. But the nature of business, the demands of customers and stakeholders are quickly outstripping the capacity of information sharing and persuasion alone to respond.

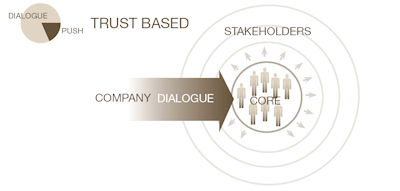

What do we mean by dialogue? I’ve said that it’s the type of conversation where two or more parties bring together information out of which something new is created.

Poet David Whyte has talked about this type of communication in terms of what it means to be a leader today. In a video on his website he talks about the conversational nature of reality:

“The conversational nature of reality has to do with the fact that whatever you want to happen will not happen. A *version* of it will happen. Some aspects of it will happen. You will be surprised also and quite often gladdened that what you wanted to happen in the beginning actually didn’t happen and something else occurred. Also it’s true that whatever society, or life or your partner or your children want from you will also not happen. They also will have to join the conversation.â€

Whyte’s speaking engagements with companies on the conversational nature of reality have to do with what kind of leadership stance one can take in response to this dynamic. Who do we need to be as leaders to participate in the conversational nature of reality?

The same question faces organizations. What kind of stance do we need to take with our customers and partners in order to thrive in the conversational nature of reality? Many companies who have been early pioneers of collaboration and co-creation will say there’s tremendous potential return on investment from engaging in dialogue. Strategy– including communications, product innovation and more – is at its best in dynamic collaboration with customers and other stakeholders. To tap that potential we need to start from a place of strong core of identity and purpose, and then have the skills and tools to support dialogue as it scales through the organization.

The scale of dialogue takes place on a continuum of complexity. On the left side of the X axis we have dialogues one-to-one; on the right side we have dialogues one-to-thousands or even millions. On the left side of the continuum we rely on interpersonal skills and good facilitation of conversations to get to the shared creation. On the right side, we need technology platforms (crowd sourcing, social media and corporate social platforms) to support true two-way “conversation†on a mass scale.

All along the continuum, we need to be able to relax our grip on our own ideas and be open to what we can “create together.†In his video, Whyte takes issue with what he calls the “strategic†approach, by which I think he means predetermining a set of actions and getting too attached to them in ways that ignore the conversational nature of reality. I would say that the type of strategy – marketing and organizational — that actually works today is one that takes the conversational nature of reality into account. It is not static. It is not a fixed plan. Rather it’s a framework that includes a strong purpose and identity and that creates a container – much like a greenhouse – where the seeds sown in dialogue can take root and grow.