Sustainability and the Path to Transformed Marketing

By Kathleen M. Hosfeld

Many are the challenges facing today’s marketing practitioners as they seek to cultivate relationships with customers in a volatile economic climate. As a chief point of contact between the company and its customers, marketing is a place where trust is either won or lost. As many consumers cut back on spending, trust is one of the critical factors underlying purchase decisions. But research shows that decades of intrusive, coercive demand-creation efforts have created layers of resistance that are now compounding companies’ woes.

Is sustainability a business strategy than can transform marketing practice and begin the process of rebuilding trust? Sustainability, for the purpose of this article, is the management of an organization’s performance in service of financial, social and environmental objectives, with the intent of meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” (Brundtland World Commission).

Transformed marketing is the emerging model of marketing practiced by high-integrity organizations, a subject I wrote about in The Transformation of Marketing. The relationship between transformed marketing and sustainability depends on the ultimate goal of both initiatives – for businesses to operate profitably in ways that create benefit for many diverse stakeholders. In early stages of sustainability adoption, however, this shared interest may not be quite as evident. As engagement with sustainability deepens, the qualities of transformed marketing begin to appear.

What are the Stages on the Road to Sustainability?

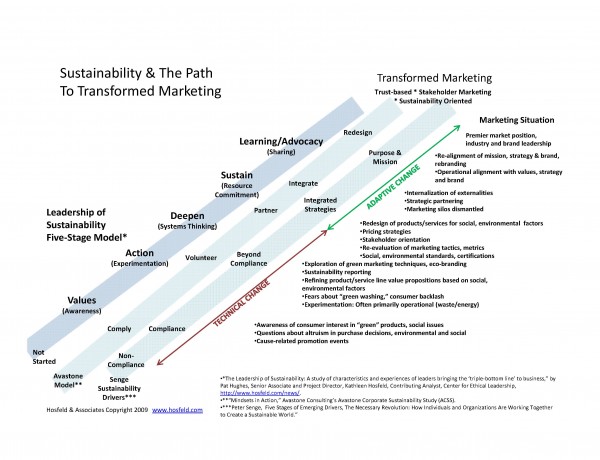

The notion that organizations implement sustainability in stages of increasing engagement is held by a variety of consultants and thought leaders. The Leadership of Sustainability, a study authored by Pat Hughes, (to which I was a contributing analyst) offered a five-stage model of sustainability development based on interviews with leaders from diverse companies. The five stages in that model were:

- Stage 1: Values (Awareness) Develop the will to take action.

- Stage 2: Action (Experimentation) Begin with a single project or experiment.

- Stage 3: Deepen (Systems Thinking) Explore implications of sustainability for all operations and decisions.

- Stage 4: Sustain (Resource Commitment) Commit to comprehensive plan with resource allocation (management focus, money), tracking and reporting.

- Stage 5: Learning and Advocacy (Sharing) Leadership and advocacy in industry; continuous learning.

Since the publication of The Leadership of Sustainability, at least two other staged models have been published highlighting different aspects of organizational engagement with sustainability. Peter Senge’s organization offers a model that describes the emerging “drivers†that push organizations deeper and deeper into engagement. Avastone Consulting offers a model that describes similar stages of engagement from the perspective or organizational perspectives or “mindsets.â€

While not in exact agreement, these three models offer a surprisingly congruent picture of increasing degrees of intention and engagement.

Marketing’s Transformation on the Sustainability Road

Each stage of engagement with sustainability presents its own marketing challenges and opportunities. See Diagram . Large Format PDF Early engagement with sustainability is focused primarily on operational and administrative changes that reduce waste and conserve energy. The primary goal of most companies in the early stages is to save money.

. Large Format PDF Early engagement with sustainability is focused primarily on operational and administrative changes that reduce waste and conserve energy. The primary goal of most companies in the early stages is to save money.

At the Awareness Stage, marketers become conscious of consumer interest in “green†products and the role of environmental and social issues in purchase decisions. There’s also increased interest in cause-related promotion events that may have an environmental or social justice focus.

At the Action Stage, companies’ experiments with sustainability may not yet translate well into promotional or brand messages. Still, marketers begin exploring how to leverage the value of these experiments for marketing purposes. They start to explore “green marketing†techniques (those tactics that have an environmental impact) and eco-branding (building environmental values into brand image). They may explore the process of publishing sustainability reports, and take more concrete steps toward refining product/service line value propositions based on social, environmental factors. At this stage, they are also concerned about accusations of “green washing,†in which companies are accused of promoting superficial efforts of sustainability merely for their image/PR benefits.

At the Deepen Stage, however, both the organization and its marketing team are invited into the initial stages of what may lead to deep change. At this stage, the leaders we studied began to see the interconnections between their operational waste and energy strategies and “everything else.†They started to see the impact of such changes on their vendors or suppliers. They began to see the potential response from community partners. They start to see the opportunities for collaboration in the community and industry to accomplish sustainability goals. According to other models, at this stage, companies also begin to see the opportunity in developing entirely new business strategies that integrate sustainability. Here we see a form of stakeholder marketing start to take hold as companies realize they have to manage increasingly deeper levels of conversation with the community, vendors, suppliers, and industry colleagues, not to mention customers. New business opportunities begin to emerge as companies realize consumers’ interests in seeing social and environmental criteria integrated into the company’s core products and services.

As a result, marketers who step up to the challenge may find themselves with new opportunities to lead conversations about the redesign of products/services for social, environmental factors and articulation of new pricing strategies. Design and pricing conversations lead invariably to engagement with standards and certifications that assure truthfulness in marketing claims. As they begin to appeal to customers with sustainability oriented values, they’ll also be challenged to re-evaluate marketing tactics that are perceived as coercive or intrusive. And as companies grapple with multiple stakeholders and holding financial, social and environmental values simultaneously, they may determine that the metrics they’ve historically used are no longer adequate.

The Shift from Technical Change to Adaptive Change

As companies and their marketers continue to deepen their engagement, the changes that they are asked to make move from technical change to adaptive change. In technical change, we don’t fundamentally alter how we work. We add knowledge; we make incremental improvements in what we are already doing; and we stick basically to the strategies we’ve been using.

On the journey to sustainability, as in the path to transformed marketing, there’s a point where we are asked to begin to think differently about how we work. Fundamental assumptions are challenged. We embark on new initiatives and enter new territory where few have gone before us. We have to take risks and learn together.

At the Sustain level of engagement, for example, marketers that have never before had to account for externalities in their pricing or product design strategies must now reframe the entire cost/value proposition of products and brands. An externality is a cost that occurs as a result of a commercial transaction that is not directly paid for at the time of purchase (the cost of waste disposal of an obsolete machine is one such externality).

Embracing the rationale for why companies should account for externalities is the right thing to do is a radical reframe of the role of the business for many. At this stage, companies also commit resources to developing strategic partnerships and fostering internal and external collaborations that bring additional expertise to bear on specific tasks.

At the Learning/Advocacy stage, companies are beginning to hit their stride in sustainability and are thinking about their businesses in fundamentally different ways than they did at the beginning of the journey. Sustainability is not something they “do,†it’s part of their core identity. As a result, marketers are often engaged in processes to rebrand and reposition the firm and its offerings in light of this full commitment. Additionally, companies are increasingly seen and act as thought leaders in their industries – advocating for sustainability practices, and sharing knowledge about their experiences. Creating open standards and sharing expertise, rather than protecting company secrets for competitive advantage, is one of the adaptive challenges of this stage.

Arriving at Transformed Marketing

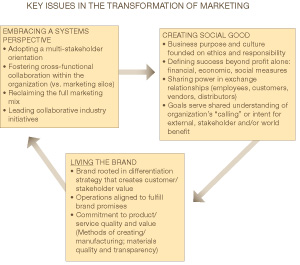

At the Deepen, Sustain and Learning/Advocacy stages, we see an acceleration of change that results concurrently in transformed marketing. Changes that took place prior to these stages were necessary precursors to the adoption of transformed marketing. These changes raise the three key issues we previously outlined in The Transformation of Marketing:

Embracing a Systems Perspective – Companies began to embrace a systems perspective at the Deepen stage. An emerging web of relations and interconnections – in customers and markets, in the dynamics between community groups and strategic partners – continues to unfold for them as they gain experience.

Creating Social Good – By this stage, sustainability is less about something the firm does to make money, and has become more a way of life. The intrinsic value of building social good into the purpose and mission of the organization has become self-evident.

Living the Brand – The alignment of values, strategies and operational practices has advanced much more deeply, and as a result the company’s brand and image has authenticity and integrity. Trust is often a core brand value, and the company’s promotional practices are measured against that value.

At this stage of engagement, the coercive, intrusive, unethical and wasteful practices that undermine marketing have been eliminated by engagement with the values of sustainability. Additionally companies have cultivated relationships with stakeholders that allow for timely feedback on whether company practices are compromising brand promises or shared values. This feedback allows the company to self-correct more quickly and restore balance and integrity to its marketing practices.

The Road Less Travelled

The current business and political interest in sustainability makes this path toward the transformation of marketing likely the road more travelled. Some companies that currently practice high-integrity marketing did not get there via sustainability, but rather through an ethic of care for all people they touch in their day to day interactions. As I wrote in The Transformation of Marketing “we are fortunate in this time that research… is confirming their collective hunch that a seemingly radical commitment to marketing that works for all also turns out to be a good way to make money. “

As always, we invite your comments, experiences and stories. Please write to us.

See the related article: Fulfilling Sustainability’s Potential: Growing the Top Line – about the role of marketing in creative strategic sustainability innovation.

about the changing nature of strategy and marketing in the “Twenty-Tweens” (our current age), I described three different forms of communication – information sharing, persuasion and dialogue. Information sharing and persuasion are the two forms most people associate with marketing. But the nature of business, the demands of customers and stakeholders are quickly outstripping the capacity of information sharing and persuasion alone to respond.

about the changing nature of strategy and marketing in the “Twenty-Tweens” (our current age), I described three different forms of communication – information sharing, persuasion and dialogue. Information sharing and persuasion are the two forms most people associate with marketing. But the nature of business, the demands of customers and stakeholders are quickly outstripping the capacity of information sharing and persuasion alone to respond.

.

.  , I frame three “Key Issues” for transforming marketing, and some (but not all) of the factors they represent.

, I frame three “Key Issues” for transforming marketing, and some (but not all) of the factors they represent.