An emerging model from high-integrity organizations

By Kathleen M. Hosfeld

The phone rings at our house on any given evening. A member of our family looks at the caller ID. “It’s Evans Glass,” he or she calls out to the rest of the house. The call goes unanswered. This is one of between four to 10 calls we receive from Evans Glass each week. We made the mistake once of talking to someone going door to door offering estimates for window replacements. When we found out that the estimate process would take two hours, we said, “No, this isn’t what we want.” We asked that they not contact us again. They have continued to call. And call. And call.

This is one of the practices that have led to another kind of call – a call to “reform” marketing. These and other common marketing practices “work” for companies – they do result in sales. However, research shows that there’s a long-term consequence associated with intrusive and coercive tactics: cynicism and resistance on the part of consumers. Studies by the American Association of Advertising Agencies and Yankelovich show that from 1964 to 2004, the number of people who say their feelings about advertising have become negative grew from 15% to 60%. Forty-five percent of consumers say that the amount of advertising they are exposed to every day detracts from their experience of everyday life (Yankelovich). Yet, companies are spending more to overcome resistance, doing more of that which created the resistance in the first place. This is a vicious, self-perpetuating cycle.

What’s to stop it? Some believe that more regulation is the answer. While regulation and public policy always play an important role in systems change, a change from within – a transformation – will ultimately reach parts of the system that regulation can’t touch. Pioneering firms have been blazing this trail for almost two decades and research is starting to show that companies that take a higher road are achieving higher returns as a result (Studies by Sisodia, Raj, Jag Sheth, and David B. Wolfe in 2007; Sully de Luque et al. in 2008; Kearney in 2009).

The Emerging Model

Consider this article an introduction to a much wider conversation about how pioneering firms are transforming marketing. To start that conversation, I’m offering a 50,000 foot level management perspective of the model of marketing that is emerging as an alternative to the vicious cycle described above. This includes sustainability and the triple-bottom-line, but this is not a model of sustainability marketing per se. It’s meant to suggest a model of marketing that is emerging in companies who have made sustainability a way of life and are continuing to evolve. I have avoided references to tactical execution and, for now, case histories. I’ve avoided elements that might be more appropriate for specific industries (hard goods manufacturers), and tried to synthesize elements that are universal to all firms.

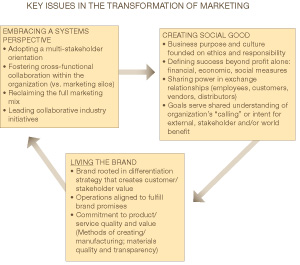

In working with clients, I often translate assessments into “Key Issues” for the sake of simplifying what must be addressed to accomplish their objectives. Key Issues are sheltering wings under which a variety of other issues or factors can find a home. In the following diagram and text , I frame three “Key Issues” for transforming marketing, and some (but not all) of the factors they represent.

, I frame three “Key Issues” for transforming marketing, and some (but not all) of the factors they represent.

A Fundamental Assumption: The most important difference between companies that are transforming their marketing practice is their interpretation of the purpose of marketing. In traditional practice marketing is about “selling stuff.” This follows the perception of the purpose of the business, which is to create profit. In firms that are transforming or have transformed marketing, marketing is about creating value for stakeholders – not as a means to an end (profit) but rather as the end in itself. Within this shift, profit is the measurement of how well the organization is achieving that end.

Embracing a Systems Perspective – A competence required for this emerging model is the ability to navigate complexity and engage with diverse, complex, adaptive systems. In transforming marketing, this includes issues such as:

Adopting a Multi-Stakeholder Orientation – In transformed marketing, the organization enlarges its focus from stockholders to stakeholders who include investors, employees, customers, partners and society. The intent is not to “manage” stakeholders but to serve them.

Cross-Functional Collaboration – In the traditional paradigm, marketing is frequently siloed and given increasingly tactical focus. In transformed marketing, value creation for stakeholders (marketing) is everyone’s job and requires cross-functional collaboration across departments – finance, human resources, manufacturing.

Industry Collaboration and Partnerships – Organizations transforming marketing are not isolated competitors seeking dominance and hoarding information. Rather they participate in industry collaborations to advance standards or other initiatives for the benefit of stakeholders.

Reclaiming the Marketing Mix – In traditional practice, marketing has increasingly focused on sales and promotion due to an emphasis on measurement. Organizations that are transforming marketing seek to maximize stakeholder benefit through all aspects of the marketing mix (product, price, promotion, distribution/sales). These marketing decisions may not take place in the marketing department per se but through cross-functional collaboration.

Creating Social Good – A radical departure from serving simply the profit motive, to one that says profit is the measure of how much value or benefit the firm creates for stakeholders. This includes issues such as:

Purpose and Culture Founded on Ethics and Responsibility – There’s a constant focus in these organizations around “doing the right thing,” which begins with purpose and a culture that supports ethical action.

Defining Success Beyond Profit – Financial measures are insufficient determinants of success for many organizations who care deeply about their impacts on the environment, on customers, on employees, vendors and more. Whether it’s two, three, four or more “bottomlines” – transformed marketing evaluates success in more than financial terms.

Organizational “Calling” – Those practicing transformed marketing are guided by goals that serve a shared understanding of the organization’s “calling” or intent to create stakeholder (or world) benefit.

Sharing Power in Exchange Relationships – Transformed marketing seeks to create partnerships with stakeholders in which power is shared. This capacity separates these organizations from those that are merely well intentioned, yet feel entitled to cajole customers into decisions that are “good for them” or to “sell what we make” without meaningful input from the customer or market.

Living the Brand – From one perspective brands are “perceptions” that are created to influence purchase decisions. In organizations practicing transformed marketing, however, the brand IS the company, and the company lives the brand. It’s not perception. It’s reality. Branding campaigns seek to create awareness of that reality, not to create it virtually. Elements of this include:

Brand Rooted in Clear Differentiation Strategy – In transformed marketing the brand is rooted in a solid business model that articulates a long-term strategy for creating value for stakeholders distinct from that of other firms. By contrast, head-to-head competition or competition on perception alone reinforces the vicious cycle of promotion to compete, leading to ethical “trade-offs”, and a firm-centric view.

Operations Aligned to Fulfill Brand Promises – The “operational side of branding” means taking the brand deeply into every aspect of the organization. This requires translating the implications of the brand for the day-to-day functions of departments. Representative questions to ask in this process include: What type of person should we hire to reflect the brand values? How does the brand change what our office looks like? How do I need to share information with other departments in order to help them live the brand?

Commitment to Stakeholder Benefit – The “right thing to do” in a transformed marketing environment is a radical commitment to making sure all aspects of brand execution translate into benefit for stakeholders. This includes ongoing reflection and action concerning methods of creating products/services, their features and benefits, the materials they use and the transparency with which the supply chain is managed.

Continuing The Conversation

Although the era of sustainability shines a brighter light on companies who practice marketing in this way, many companies – including ours and our clients’ – have been marketing in the spirit of the emerging model for years if not decades – long before frameworks for sustainability or the triple bottom line were as accessible as they are today. As more organizations adopt social enterprise models and similar forms that blend mission and revenue creation, transformed marketing offers an approach that better fits their values.

Many of the companies who have been pioneering in this model have done so based on the intuitive conviction that it was simply “the right thing to do.” We are fortunate in this time that research, including the studies referenced above, is confirming their collective hunch that a seemingly radical commitment to marketing that works for all also turns out to be a good way to make money. Many today are trying to approach the triple bottom line from a single-bottom-line perspective. Perhaps now there’s enough empirical research to encourage such firms to explore this emerging model more deeply.

There are many stories to tell and many interrelated ideas to unpack as we continue our own exploration. We’d love to hear from you about your experiences, ideas and questions.

, I frame three “Key Issues” for transforming marketing, and some (but not all) of the factors they represent.

, I frame three “Key Issues” for transforming marketing, and some (but not all) of the factors they represent.